Abstract Text

Large area (2D) and volume (3D) EBSD mapping and the associated distortion corrections

B. Winiarski1,3, A. Gholinia1,4, K. Mingard2, M. Gee2, and P.J. Withers1,4

1 School of Materials, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

2 Materials Division, National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, TW11 0LW, UK

3 Thermo Fisher Scientific, 62700 Brno, Czech Republic

4Henry Royce Institute, School of Materials, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

Introduction

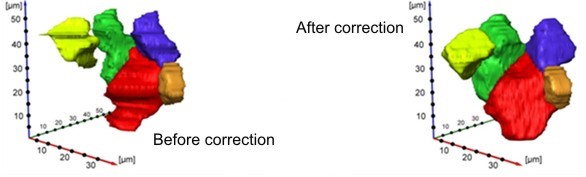

Usually, large 2D EBSD mapping as well as 3D EBSD maps by serial section tomography (SST) can have image distortions [1,2], largely because of drifts which occur over the long periods they take to acquire. In this work the drift and distortions are quantified and corrected by correlating the SE images with the EBSD maps. There are two types of correction methods proposed; one is the long-range, caused by drift, and the other is short-range, due to topographical effects. The corrected images are stacked and quantified for the visualisation of large 3D volume data. These artefacts can be significant and are usually neglected, but if not recognised can lead to misinterpretation of acquired data.

Methods and Aim

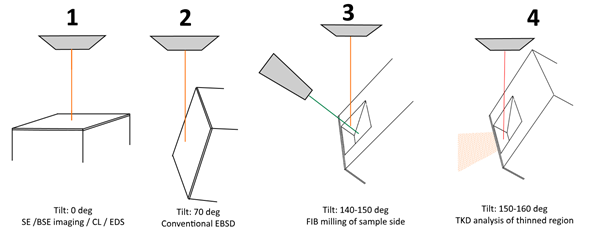

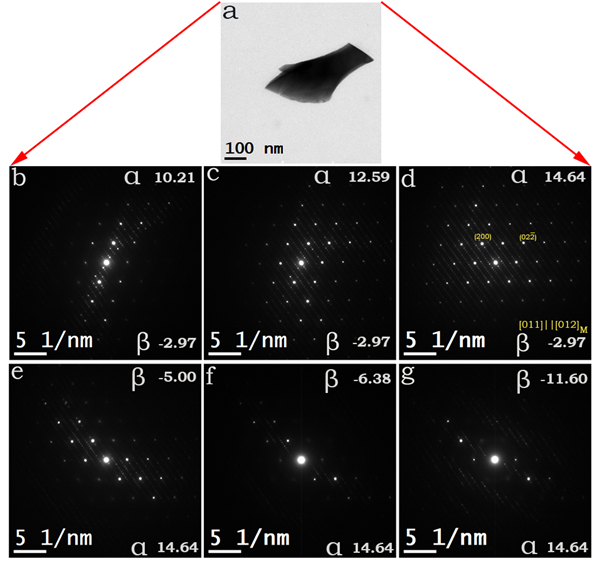

The material studied was a Tungsten carbide and Cobalt (WC-Co) hardmetal containing 11 mass % Co and having the average grain diameter of 5 mm. Broad ion beam and scanning electron microscopy (BIB-SEM) and serial section tomography (SST) was used to gather the 3D EBSD data using FEI NOVA600i FIB-SEM, Gatan, Ilion and Nordlys-S EBSD detector from Oxford Instruments [3].

The aim of this paper is to raise awareness of distortion artefacts, which are largely neglected at present, to quantify them and to show the benefits of their correction.

Results and Discussion

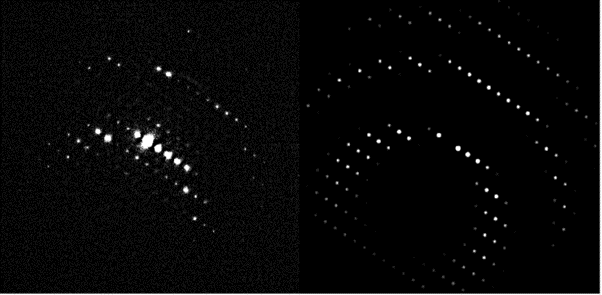

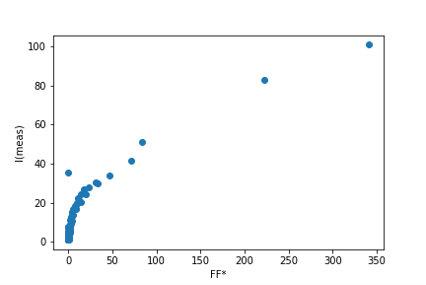

In this study the secondary electron (SE) images were used as the distortion free reference to correct the distortions in the EBSD maps. Our proposed distortion corrections methods utilise COSFIRE, Combination of Shifted Filter Responses filters [4] and Moving Least Squares (MLS) rigid deformation method for digital image morphing [5]. The aim of this paper is to raise awareness of artefacts which are largely neglected at present, to quantify them and to show the benefits of their correction.

The distortion corrections are applied to this dataset. The correction methods presented here can potentially be used at different length-scales in 2D and 3D with other SST methods, e.g. mechanical sectioning, SEM microtome, laser sectioning, FIB-SEM tomography, etc.

Conclusions

We have proposed a distortions correction method to find a solution for artefacts commonly associated with large area EBSD mapping [6]. These comprise both long-range distortions and short-range distortions. The long-range distortions can have a variety of causes, such as drift associated with the long acquisition times, scan distortions or long-range sample alignment or surface topography. The short-range distortions maybe a consequence of local surface topography, such as ‘curtaining’ typically seen during ion beam milling.

Cluster of WC grains taken from a large dataset 200um x 200um x 40um , which shows the 3D EBSD stacked data before and after the distortion corrections.

Keywords

BIB-SEM, FIB, 3D EBSD, distortion correction, serial section tomography

References

[1] G. Nolze, Image distortions in SEM and their influences on EBSD measurements, Ultramicroscopy. 107 (2007) 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2006.07.003.

[2] D. Rowenhorst, Removing Imaging Distortions Through Automatic Stitching of EBSD Mosaics, Microsc. Microanal. 19 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1017/s1431927613006193.

[3] B. Winiarski, A. Gholinia, K. Mingard, M. Gee, G.E. Thompson, P.J. Withers, Broad ion beam serial section tomography, Ultramicroscopy. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2016.10.014.

[4] G. Azzopardi, N. Azzopardi, Trainable COSFIRE Filters for Keypoint Detection and Pattern Recognition, IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35 (2013) 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2012.106.

[5] S. Schaefer, T. McPhail, J. Warren, Image deformation using moving least squares, ACM Trans. Graph. 25 (2006) 533. https://doi.org/10.1145/1141911.1141920.

[6] B. Winiarski, A. Gholinia, K. Mingard, M. Gee, G.E. Thompson, P.J. Withers, Correction of artefacts associated with large area EBSD, submitted to Ultramicroscopy 2021.